The most famous Syrian refugee lives between Lebanon and France since 1956. The poet who modernised the Arabic literature, a perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature, describes as “an absolute horror” the terrorist attacks that rocked Paris last November [2015]. The neighbourhood where he lives was one of the potential targets. “I hope that, from now on, there will be more people accepting the need to separate state and religion”, he said. (Read more…)

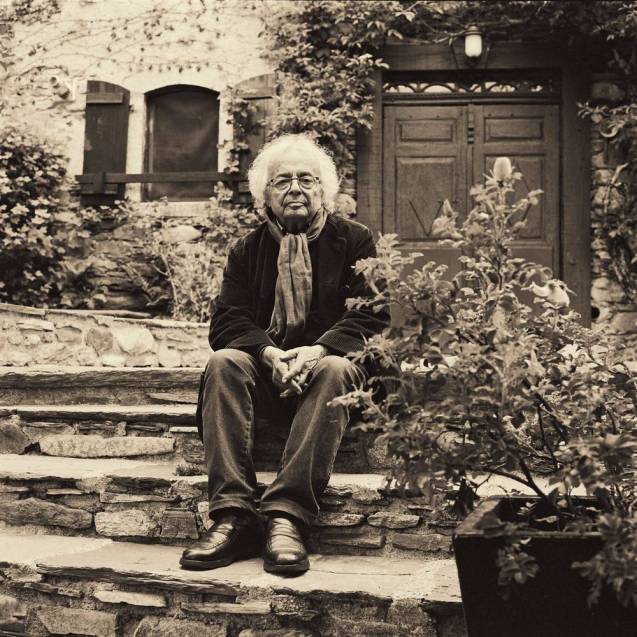

Adonis (or Adunis), pen name of Ali Ahmad Said Esber

© British Library

It is in a concrete and glass tower, 104 meters high with 308 apartments, La Tour Gambetta, in La Defense, that the renowned Arab poet Adonis lives and works. And it was here, in the largest financial centre of Paris – and of Europe – that a 27-year-old terrorist responsible for the worst attacks in the French capital since World War II (130 dead and 350 wounded) was planning to blow himself up.

The suicide bombing in La Defense was scheduled for the November 18 or 19. It was going to be committed by Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the “brain” and financier of the Friday the 13th massacres, French prosecutor François Molins said. Of Belgian and Moroccan origin, this member of the self-proclaimed “islamic state” (Daesh) had returned from Syria and was killed, precisely on the 18th, during a police siege in an apartment in the Saint Denis area.

On the 13th, Adonis was at home when he learned, on television and in calls from friends, about the co-ordinated attacks, with bombs and machine guns, in six sites of Paris, from the France Football Stadium to the Bataclan Club, where 1,500 people were attending a rock concert.

Most of the victims were killed here, some executed in cold blood. “I was horrified – it was an absolute horror”, said the Syrian writer in a telephone conversation, which completed an interview that he had given me, in Paris, last September.

“Perhaps, these criminals are not believers, and I agree that a vast majority of Muslims are disowning them, but the criminals have been claiming the right to “call on the name of the Lord”, and we can’t ignore this reality.”

“Perhaps I will now be taken more seriously when I insist on separating state and religion, as soon as possible. Otherwise, we will not advance into the future. I’m more convinced than ever that organised religion is the internal colonisation of the human being.”

“I did not give up my fight against fundamentalism, Islam and other religious laws that oppress all of us, and women in particular. We will advance towards progress only after women gain their freedom.”

President François Hollande promised a “ruthless response”, and Adonis was “very happy” when France started to shell positions of the Daesh.

“We have to be realistic: the policy of the West for Syria has been a complete failure. A military intervention is long overdue, like the one unleashed by Russia which has my full support. Europe reacted too late [to the Islamist danger].”

“I do not support Bashar al-Assad’s regime, which is largely responsible for the country’s destruction, but their opponents are not innocent either. Breaking with the structures of the past has to be our priority, and not only to bring down a single man.”

“I’m convinced that the Paris attacks were the beginning of the end of Daesh – we can all be confident about that,” the poet said. “No, I’m not afraid to leave the house and go out to the streets. Fear is banal. Death is banal. Everyone dies. The problem is how to live, and how to defend life. Death is not the problem.”

Adonis was born in 1930 in Qassabin, a village nestled between the city of Latakia and the Assad family stronghold in Qardaha, Syria

© artphotolimited.com

Adonis’ home and his office, which he calls “the best organised disorder”, are located on two different floors of La Gambetta, with a permanent security centre at a wide entrance hall. While we wait for one of several elevators, there are many Muslim women who go up and down, their hair covered by hijabs.

It’s kind of ironic that a place rented or owned by “wealthy Arabs” of the Persian Gulf had become the second exile (after Beirut) of the poet who wants to secularize the Arab world.

On September 18, Saturday, 9:30 am, I ring the doorbell. At the entrance a smiling man appears, his grey hair more upright than usual, elegantly dressed in blue jeans, a black corduroy jacket to match a striped shirt and a scarf in various shades of pink.

I am invited to sit down in one of the sofas of a living room packed with hundreds of books. The walls are covered with paintings, his own and of personal friends. Magazines, letters, papers, pens and pencils, and a box of baklava, traditional Turkish sweets, are randomly displayed on a table in front of host and guest.

Adonis has just returned from Ankara and Izmir, and he has his bags already packed for a conference in the United States.

His wife, literary critic Khalida Esber, had been hospitalised the day before. He has a serene expression on his face, as serene as the music we hear on a small radio. The sun enters with its radiant energy through one of two windows.

“You know my story, I do not need to repeat it, right?,” says the son of peasants to whom his parents gave the name of Ahmed Said Esber when he was born in 1930 in Qassabin, a village nestled between the city of Latakia and the Assad family stronghold in Qardaha, Syria.

He does not believe in deities but “Adonis” was the name he gave himself at the age of 17, inspired by the Greek myth of the Greek-Phoenician god of fertility.

He was frustrated that no publication was accepting his poetry and articles. How could they ignore the youngster who, at 13, made such a good impression on the first post-independence President of the Republic when he declaimed his first poem in front of him? His reward was a scholarship at the Lycée Français of Tartous.

A perennial contender for the Nobel literature prize, Adonis was already familiar with the classical Arabic and pre-Islamic poetry, and the works of Baudelaire, Rilke, Char and Michaux when he graduated in Philosophy at the University of Damascus in 1954.

In 2011, he was awarded the no less prestigious Goethe Prize (one of many in a seven decades career), recognised as “the most important Arab poet of our time.”

Adonis has a delicate and indomitable personality. Here he is, the Syrian Socialist who first fled to Lebanon in 1956, after eleven months in jail on charges of subversion for opposing “the totalitarian ideology” of the Ba’ath Party, and who, in 1985, during a civil war, looked for shelter in France.

Here he is, a good friend of the late Palestinian national poet Mahmoud Darwish (1942-2008). Both introduced new Arab talents in literary magazines that Adonis directed – Chiir and Mawáqif.

Here he is, the writer who blessed the 2011 “Tunisian Spring”, but refused to support “a revolution coming out of mosques” in Syria. Because, he says, all Arab dictatorships and not only the one in Damascus have to be toppled – peacefully and not by force.

Invited to his Parisian home, I came in with one of Adonis’ most important books, Chants of Mihyar le Damascene (Gallimard). After a five-hour interview, I was offered one of his “indecipherable” paintings, and an anthology of his poems in Portuguese (selection and Arabic translation of Michel Sleiman, introduction by Milton Haitoum; Companhia da Letras, Brazil).

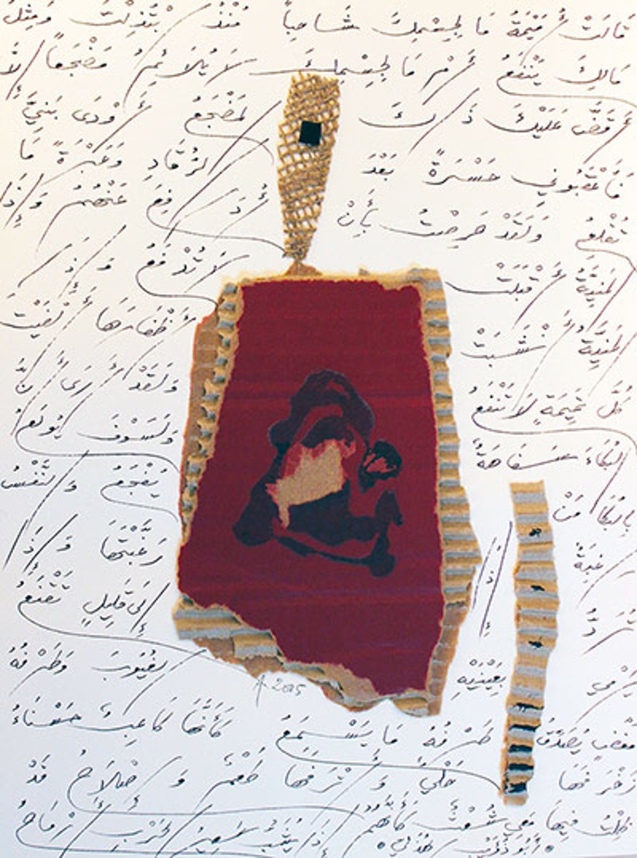

Untitled 2005: “The text is from a pre-Islamic poet, Abu Zu’aib Al-Huzali which speaks of his life and loves. The cardboard comes from a torn-up box of books”

© Adonis | The Guardian

You are 85-year old and your energy seems inexhaustible. You’ve just arrived from Turkey and you’re already preparing for another trip. How is your daily routine?

I have this energy because I feel that I have something to say. I live to work. I have no rules. I am totally free. There are days when I work in the morning; in other days I don’t.

I do not follow any discipline, like other writers. I wonder how writers have an organised life: an hour to write, another to eat, another to read… I am against any planning. From time to time I like to do nothing. I’m just quiet, listening to music…

You were listening to music when the door opened…

Yes, I was listening to classical music, my favourite. When I’m a little lost, I love listening to Beethoven. Mozart… for when I’m sad or joyful. I also love Bach.

Music and words, what defines you better?

I do not fit in any category. Definitions distort things. Things are open; to outline them is to close them. Only two words are meant to be definitive, “religion” and “ideology”. And I oppose them because a word is a search for infinity.

Aren’t you defining yourself as a poet?

Oh, yes, I am a poet! And I speak as a poet. But poetry is not just about writing poetry. Poetry speaks of problems – does not offer any solution. Poetry is a thought.

All great poets have been or are great thinkers. One of them was the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. Pessoa’s poetry is one of a free thinker.

“We die if we do not believe in gods/ we die if we do not kill them.” What did you mean when you said that?

The free thinker’s duty is to create gods and to kill them immediately, in order to get a perpetual renewal.

You also said, “Military dictatorships control the spirit and religious dictatorships control the mind and the body”…

Yes, religious dictatorships kill the whole human being.

It’s not possible to reconcile religion and poetry – why? In Portugal, there is a great poet, José Tolentino Mendonça, a priest and free thinker who is admired by believers and non-believers…

…In his poetry, he is certainly an open person. He has personal beliefs. I respect the faiths of individuals. But I can’t stand when people force their religion on me.

Religion is a personal issue, like love. I am against organised religion. Do all people think the same way? No, and I refuse that. If we want a “social religion”, it has to be the one of human rights, of freedom, of brotherhood.

Untitled 2009: “This text is part of a love poem. It’s one of a series of rakaim [images of calligraphy and figurative gestures”] using my own poems”

© Adonis | The Guardian

Religion has been used as an instrument of war, and your country is a battlefield where religion serves as a source of political conflict. What are your memories of Syria?

I have many memories: the one of my village, my childhood, and the childhood of Syria – the birthplace of Europe. There is a legend, in which I believe, that this continent owes its name to the Phoenician goddess “Europe”.

Zeus turned into a bull and carried her off. And while looking for her, Cadmus, Europe’s brother, brought with him the alphabet. He did not bring war.

Syria is the cradle of great civilisations and of the three monotheistic religions. I respect these religions, even if I’m not a monotheist. What I condemn are the totalitarian aspects of religions.

But in your childhood you have studied at a Koranic school…

Yes, I was born in a religious environment [the Adonis family is Alawite, a ramification of Shia Islam], but over time I gave it up. I was then 14-15 years old. My father was friendly and compassionate. He never impose his ideas on me. He gave me some useful advice: “First think, my child, and then act.”

I have three brothers and two sisters (one passed away). We’ve always respected each other’s freedom. My mother, who died at the age of 107, was a free woman. I still have family in Syria but, unfortunately, it has been five since the last time I saw them.

You have never returned…

No. I wrote a book about what’s happening there, Arab Springs: Religion and Revolution. I keep repeating the same over and over, that we cannot create a revolution based on religion. Humanity needs a revolution that totally separates religion and state, the politics, the culture and the society. Religion should be left to the conscience of the individual. We have to take back our creative freedom.

Everyone has the right to change their mind, but Muslims are not even allowed to change their religion. Doing that would be tantamount to a death sentence. I refuse to march in a political demonstration that begins in a mosque. This is my manifesto. At the beginning, I was strongly criticised for expressing this position, but I’m getting lots of support lately.

The initial protests against Bashar al-Assad in 2011 were not religious. Syrians were demanding reforms, not regime change. However, the security forces cracked down on peaceful vigils…

…There has always been opposition in Syria. I’m a dissident since 1956! I’ve always condemned the policies of the Baath party [which had the monopoly on power in Damascus, and in Baghdad under Saddam Hussein].

The Arab Left, including the Communists, was never radical in its essence. Their main aim has been to attain power, not bringing about change in society.

Take the case of Egypt for instance: Gamal Abdel Nasser was a great leader, but we can’t find modern institutions in his legacy.

One notable exception is Habib Bourguiba [1903-2000], in Tunisia. He changed the law and gave more rights to women. Tunisia is perhaps the only country where the social fabric is not religious, where the fundamentalists know that they can be removed at any time.

We cannot make a revolution just to overthrow one single dictator. The imperative of a revolution – a peaceful, not violent one (I am more Gandhi than Che Guevara) – is to change the whole society. For two centuries the Arabs have done no more than changing regimes – but they do not change anything.

Isn’t regime change the first step?

We have changed many regimes but we are not building universities…

… Well, in Saudi Arabia, home to a strict version of Islam, the former king founded a university with no gender segregation, Qatar is hosting branches of leading English, and American universities…

…I mean universities in the modern sense, not academic institutions where religion remains the dominant force. Let us go back to what is happening in Syria.

What we see out there is not the Syrian people trying to topple the regime, but mercenaries destroying the country. This is not an independent revolution. On the contrary, it is totally under the control of foreign forces.

What we are witnessing is an invasion. Where are the true revolutionaries defending new principles for our future? The so-called “revolutionaries” al-Nusra Front, an ally of al-Qaeda, and “Islamic state” [Daesh] never speak of women, for example. It’s like if women do not exist, but it is crucial to liberate women from religious oppression.

Those “revolutionaries” also never speak of secularism. So, how can we make a revolution without questioning religion? The purpose of the foreign forces [in Syria] is to change a regime whose political color displeases them, and to replace it with a more favourable to their interests. This is a coup, and I am not interested in it!

Untitled 2008 : “This is the only collage where I’ve used black ink. It’s a text from the 8th century – another beautiful love poem – this time by Bashar ibn Burd, one of the founders of Arab modernity at that time. He was killed by the Caliph after he was accused of being irreligious”

© Adonis | The Guardian

Past Arab revolutions were more ideological than religious…

Yes it’s true. There were times of hope when I was young. Religion had no ideology, or it was practically invisible. I was never asked, “What is your religion?” Today is the opposite.

Is this a challenge for the “Arab Spring” generation?

The “Arab Spring” failed because of reactionary forces (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, etc…), and foreign interests. But I still have faith in a generation who has not given up [on reform]. Being democratic is to recognise and accept that “the other” is different. This is not to be confused with tolerance. There are racist feelings behind the notion of “tolerance”.

Democracy demands freedom, not tolerance. Christians must have the same rights as Muslims, and this can only happen when religion becomes an individual choice. Democracy should not be reduced to a slogan.

“The free thinker must always support what is revolutionary but never be like the revolutionaries.” Why did you say that?

An operative revolutionary is only focused on tactics, strategies… Not me. I’m a genuine revolutionary. A free thinker is committed to change the society, not just the regime. I express myself in the language of real revolutionaries.

I never repeat what the operative revolutionaries say, because a writer has to be a truly free person. I support the real revolutionaries, but I am alone in this revolution. Ideology is against art. I am a militant, not a partisan.

You need inner strength since your positions are somehow controversial…

Yes. When we are not partisans, we run the risk of having a lot of people against us. Some people criticise me because I don’t use their words. I refuse to repeat their slogans.

I remained a militant. In our culture, unfortunately, everything is based on the unity – of God, of politics, of the people. But you cannot have democracy with this mentality. Who owns the truth? Nobody.

![Untitled 2011: “This is the only rakima [singular of rakaima] where I’ve used a photograph. It’s a young woman protesting against the wall in Palestine. The text is an assemblage of pre-Islamic writings which speak of peace and against oppression” © Adonis | The Guardian](https://margaridasantoslopes.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/collage.jpg?w=637&h=956)

Untitled 2011: “This is the only rakima [singular of rakaima] where I’ve used a photograph. It’s a young woman protesting against the wall in Palestine. The text is an assemblage of pre-Islamic writings which speak of peace and against oppression.” Adonis says that he supports “the real revolutionaries”

© Adonis | The Guardian

At the presentation of the Goethe Prize in 2011, you made an appeal to the Arab regimes: hear “the cries of the people” or face a “catastrophe”. In Syria, the President refuses a compromise. Syrian civilians are being bombed and massacred. Syria’s UNESCO heritage sites have been damaged or destroyed…

…It is an unprecedented situation. I have never imagined that this would be possible in my whole life. Everybody is responsible – not only the regime, although it’s the main culprit.

I wrote an open letter to Bashar al-Assad [published in the Lebanese newspaper ‘As-Safir, in 2011], asking him to give back voice to the people and not use violence, and to create the conditions to impose a secular system. He ignored me.

However, I also do not understand those who fight a despotic regime only to benefit another, as the Islamists are doing.

Would a peaceful transition have been possible had Assad accepted the initial calls for political and social reforms?

When judging the Arab regimes, the Syrian – at least in what concerns the development of society – was almost the best of them all. If we want to liberate the Arabs, we must rise up against all the dictatorships without exception! Hypocrisy reigns in the West, more interested in colonisation than in human rights.

There are still monarchies in Europe – some constitutional and others merely symbolic. But they are not absolute and hereditary as the Arabs dynasties. It is too early to judge the current events in Syria. Many people have already realised this is not the revolution of their dreams. And, sadly, the regime is stronger than ever.

Why?

People are making comparisons. The regime was dictatorial – no doubt about that – but one thing is to fight the dictatorship and another is to destroy a country. The opposition needs to be strengthened.

For a long time the Muslim Brothers were the only opposition willing to become martyrs for a cause. Secular activists, like Adonis, chose exile over death in fighting the regime…

No. No! I was in prison and I was not alone. The dictatorship oppressed above all the secular and civic movements. The regime favored the religious groups. Damascus is now a forest of mosques. And it was the regime that created it, the regime that oppressed all those who advocated secularism and freedom. The regime knew how to use the believers, because the secular were a greater threat.

So, was the religious opposition strengthened with the exile of secular dissidents?

Perhaps, perhaps, it favored. I can only talk about myself: I am not, I repeat, a partisan. I’m not a politician. I am a man of culture. I am a poet. [The conversation is interrupted to answer a phone call from a friend.]

Sorry, but we are preparing the publication of Islam and Violence, which should come out in November this year, and the III volume of Al-Kitab [“The Book” – considered a masterpiece] as well. It’s a comedy like that of Dante, but his is focused on heaven and mine is on earth. It is about the hell of Arab history.

Do you still remember your first poem?

That part of my story is almost legendary. I keep on asking myself how everything was possible. What prompted me to write that poem, the certainty that the President would like it and would ask me, “What do you want in return?”, my answer, “I want to go to school”, and he accepting my request. This imaginary dialogue took place exactly as I had envisioned. So I can say I was born in poetry. I was born in classical poetry.

What does inspire you?

There is no inspiration. There is work and there is life. There is a relationship with people and with things. It is as if I had got a revelation… I am a pagan prophet.

Some subjects are always present: friendship, love, eroticism or nature…

… I write about the universe. Men are extraordinarily complicated creatures. They are wild and divine. There’s the man who beheads another man. There’s the man who opens to humanity. I love all my poetry. If I did not love it I could not write it.

I write about the demons of the Arabs, from an internal, not external perspective. We are living in a culture that leaves no room for questions. Not even God has the “right of answers”. (Laughs)

A father speaks with his children in an underground Roman tomb which he uses with his family as shelter from Syrian government forces, at Jabal al-Zaweya, in Idlib province, on February 28, 2013. The ancient sites are built of thick stone that has already withstood centuries, and are often located in strategic locations overlooking towns and roads

© Hussein Malla | AP

Where was your poetry born?

At home, and on the street, at day and night… There is no specific time for poetry or for love. All my time is for poetry and for love. It does not matter when, where, how.

Have you been influenced by other poets?

It is essential to have a personal and particular light. We can add this or that , but poetry is vertical. It is not linear. It must come from within. Only then every word is built. Each poet has his own space.

Only bad poets imitate phrases or images. For example, if I like Goethe or Dante, I will not do exactly like them. Their influence compels me to create a totally different world from them, a world of my own. That’s my only poetic influence. To mimic a culture is a commonplace.

That’s why you’ve decided to “rewrite” the entire Arab literature and poetry…

…A poet could not have done otherwise. I broke with the past. I revolutionized the order of things. That’s what matters to me. The Arabs are not equal in their language, and they are aware of this. I often say that Islam became a religion without language and without culture.

Those who listen to the Koran are now more than those who read it. But Arabic is not just music. It has body, voice, dreams, and imagination… One more problem: there is no philosophy or philosophers in the Arab world. There are no psychoanalysts, and we are more in need of Freud than of Marx. Arabs are consumers of Western modernity, but they still refuse its rational principle.

Who are your favourite poets ?

My first poet was a philosopher, Heraclitus [535-475 BC, approximately]. It was he who said that we can’t dive twice in the same river. I love very much those who are not poets in the classical terms. Nietzsche was a great poet.

I love the ancient texts of the Latin poets, the Romans and the Greeks. Of modern poets, I love Rimbaud, Baudelaire [that Adonis translated into Arabic], because they were both critical of the established order, especially religion. I don’t like to speak of those who are still alive, but I really love the classical Arab poets like Ibn-Arabi, Abu Nuwas and al-Niffari, who were much more revolutionary in their time than Baudelaire was for Europeans.

However, I rediscovered Abu Nuwas by reading Baudelaire. It was by reading the Surrealists that I have understood the greatness of al-Niffari, a rebel against religious institutions.

Nawas and Niffari changed the aesthetics and beauty of the Arabic language. They expanded the concept of poetry. They revolutionised the Arabic language, the Arabic poetic language.

A Syrian street vendor who sells cigarette boxes, sits in front of destroyed shops which were damaged by the shelling of the Syrian forces, at Maarat al-Nuaman town, in Idlib province, on February 26, 2013. “Many people have already realised this is not the revolution of their dreams,”Adonis says

© Hussein Malla | AP

Do you always write in Arabic?

Yes. It is my mother tongue. Arabic is more than my skin. It’s the body. You cannot translate an Arabic classic poem – because to translate is to destroy it. Translation is like a new creation. And yet, even if it is “a betrayal”, we need to translate.

Do you write your poetry on the computer?

Never! My wife uses the computer to type my handwritings. I cannot imagine a machine separating the poem from the body. I have so many notes that it is impossible to quantify them.

When feeling tired, I prefer to write prose instead of poetry. For the last ten years, I have also been dedicating myself to design and to collages.

How did you start?

It was by chance. Sometimes I find it hard to read or write. So, many friends and a few painters asked me, “Why don’t you try something [different] in your spare time in the spirit of poetry?” And I tried to do something rather than do nothing because there was a time when I stopped doing everything.

Then, I had to start over. Michael Camus [1929-2003], a friend who has already passed away, saw my collages and asked: “Who did this?” I replied, “It was another friend.” And he added: “I have to know that friend.” I had to concede: “I did it.” He was always by my side, and organised some exhibitions.

What does “exile” mean to Adonis?

We are all exiled, because living in this world is not our choice. We do not choose our parents or the place where we are born. A free thinker is always establishing a distance between himself and the others. When we move away from home, we understand our country much better.

We are exiled in our own language. For a free thinker, exile is a natural state. I could not write and live without this distancing. The same happens with love: only two lonely bodies can make love.

There is no motherland/fatherland…

…Our country is where we write – it’s not geography. Human life is the greatest asset. That is why poets see themselves as brothers, regardless of their language, nationality or country.

Between my exile in Beirut and Paris, there is only a difference of degree. In France, it is a more restful and open environment. In Lebanon, it is more intimate and natural. Perhaps, in a sense, Fernando Pessoa is closer to me than an Arab poet.

A Syrian refugee boy poses with his newborn brother as their mother lies near them in a house in the Basaksehir district of Istanbul, on March 4, 2014. Syrian government forces are waging a campaign of siege warfare and starvation against civilians as part of its military strategy, a UN-mandated probe said on March 5. Syria’s war has since March 2011 killed more than 140,000 people and forced millions more to flee.

© Gurcan Ozturk | AFP

What do you know of Portuguese poetry?

I know Miguel Torga and Nuno Júdice, but not very well. As for Fernando Pessoa, I read him as an incomplete man in search of himself. I feel that he also repeats himself. He says in two pages what he could have said in two lines.

The Arabs are like that. I’ve just changed that a little bit. I believe that by living and loving we do not need to use many words.

I’m not criticising. I do not like to judge or to insult. On the other hand, I love having enemies, provided that they are not ignorant. A great enemy is like a good friend. A great enemy respects us. Only petty people who have nothing to say are disrespectful to others. Bad poets condemn, the great ones forget.

You were the first Arab writer to win the prestigious Goethe prize, and you have been a “perennial contender” for the Nobel prize in literature. In 1988 you were a betting favourite but the winner was the Egyptian Naguib Mahfouz. Since then you have been in every list…

…Mahfouz was a great writer and I liked him a lot. I do not care about the Nobel. To be honest, I do not seek this glory. The prize money, though, could help me to have a less difficult life – because I have to write and travel a lot.

[We are now in the studio, two rooms – one for his paintings and collages, and another that serves as storage. More books, photographs, newspapers, frames, records, relics… are everywhere. We have to be careful. One misstep and some treasures might be lost.]

On this wall there are two photographs of Portuguese José Saramago, recipient of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Literature. Have you read some of his books?

None! To be honest, one of my daughters appreciates Lobo Antunes more than Saramago, but I’ve never read him either. These pictures of Saramago embracing his wife [in Lanzarote, Spain], I put them on the wall because they are beautiful, and they express a love relationship.

[Pointing to a postcard] They are like this image of The Origin of the World by [Gustave] Courbet. Many people where in shock when it was painted [in 1865] because it shows the genitalia of a woman.

I like to write about the body – marginalised, oppressed, hidden by religions. If you do not know your own body, how do we get to the “other”?

Are you afraid of death?

It is often necessary to die in order to live. I don’t fear death. I’m only scared of dying if I leave behind an incomplete poem.

How do you expect to be remembered by the Arabs?

I do not care how I will be remembered. My only interest is to create what the Arabs do not know or they have never met.

A great poet does not write for others. He writes to better understand himself and to better understand the world. I do not write to leave a message. I write in order to be a place of encounter with others.

This article, edited for clarification and updated, was originally published in the Portuguese news magazine VISÃO, on December 3, 2015